Vermont City Marathon 2019 Race Report

It’s been 2 days, 22 hours, and 21 minutes since I crossed the finish line of the Vermont City Marathon. It’s just long enough now that I can start to distance myself from it, but not long enough that I’ve forgotten.

Nothing prepares you for a bad race, especially if you’ve never had one. It may sound unwarranted, but a bad race requires mourning. And you don’t have to let anyone try and convince you that it’s not a big deal. A bad race is personal and it hurts. Especially, a marathon where months of hard work crumbles in a matter of minutes.

No one else can relate to that feeling unless they’ve been through it.

In the past, being on the other side of this, I’m usually the one to say that you can learn a lot more from a bad race than an easy one where everything went according to plan. And I know that, regardless of what just happened, I have more miles on my legs than before I started and I’m mentally more prepared having gone through it.

I’ve spent enough alone time in the last 36 hours to wallow in the details: the course I chose, my training preparation, fueling, strategy, race day expectations… there’s only so many ways the pieces can come together again. The thing is, I just came off one of my best training cycles leading up to a marathon. I ran long hard tempos every week, strength trained regularly, and not once did I get sidelined by injury. You bet I’ve been itching to sign up for another marathon, but I won’t.

Now that I’m feeling less broken, let’s go over what happened.

Training: There were a lot of things that went well during this training cycle and a few critical things that didn’t.

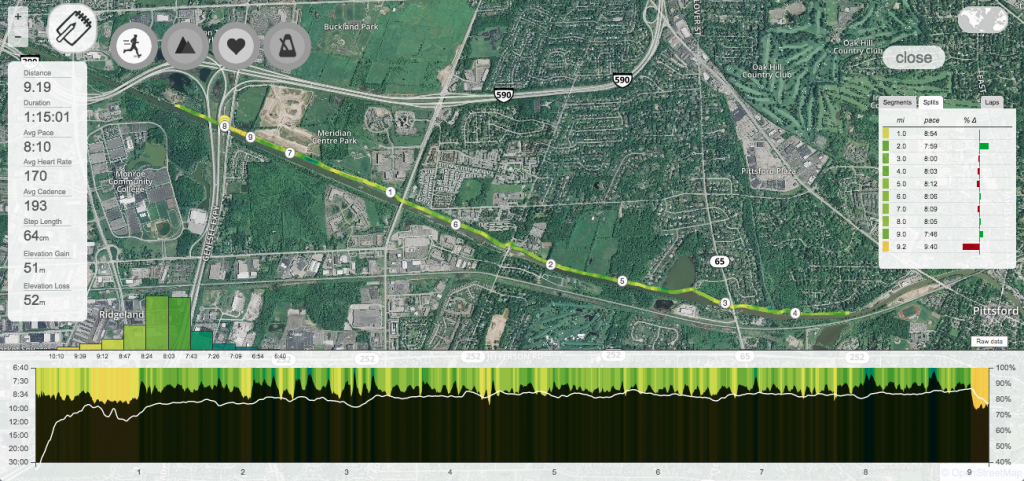

I used the Hansons Marathon Method to prepare for Burlington. It’s similar to Jack Daniels’ 2Q method in that you have 2 quality runs each week. Hansons’ quality runs are called SOS – something of substance – and consists of one speedwork or strength work and a long tempo. The long runs are also “easier” in that you only have to build up to 10mi, and then you’re more or less going back and forth between 10mi and 15mi until you peak at a 16mi long run.

On Hansons, you run 6 days a week, with the speed/strength on Tuesdays, tempos on Thursdays, long run on Sunday, and take Wednesday off. That means, when you do your speed or strength work, it’s on the back of your trailing 5-day volume including your long run. Afterwards, you get a day’s rest and then bang out a long run at threshold when you resume. It is hard work.

To clarify some differences between the two SOS runs and your tempo. Speedwork is anaerobic effort. It’s burning legs and heaving lungs type of acute discomfort.

Strength work is 10s slower than goal marathon pace. It’s more of a slow burn; a gradual build up of lactic acid at each repeat. Or as Luke Humphrey describes it, it’s “a fine line between being a sustainable effort vs. crashing and burning.”

Tempo, as defined in this method, is your goal marathon pace. And with Hansons, you spend a lot of time running at this pace with your last 3 tempos being 10mi each.

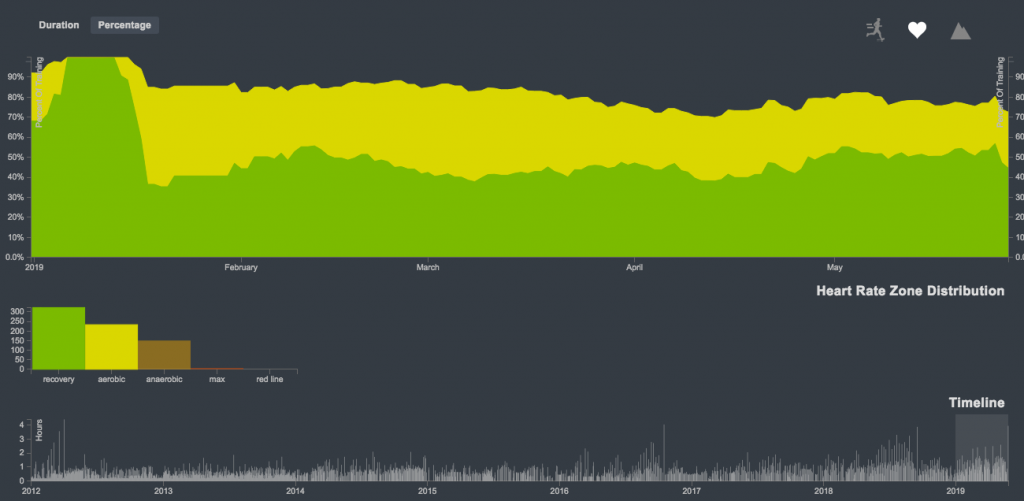

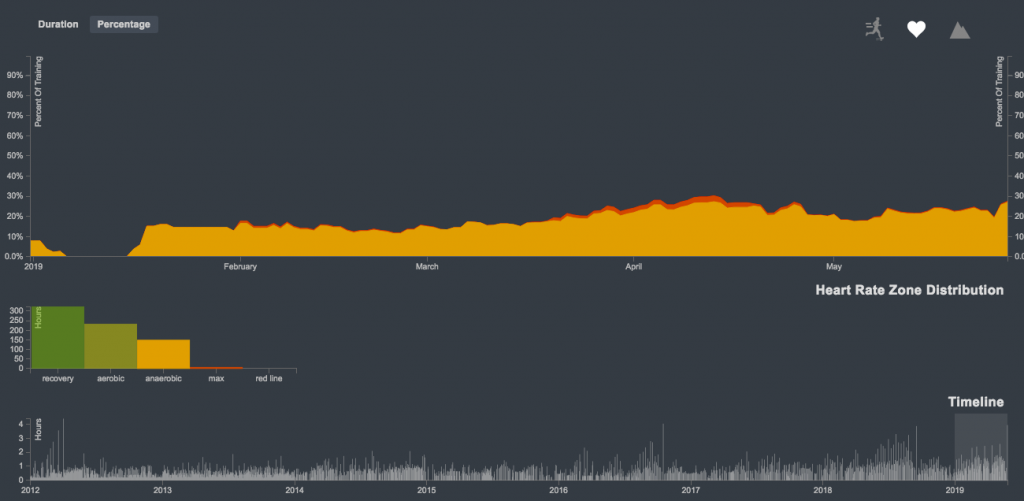

I did really well on Hansons, and I liked it even more than the 2Q method. I transitioned from 40mi to 50mi weeks without any trouble, adapted quickly to running weekly tempos, strength trained at the gym 3x a week, and had zero injuries, which has never happened before. And my HR distribution was about an 80/20 split between aerobic and anaerobic from when I started the training plan until I finished.

Most of my preparation went according to plan with the exception of week 8, 11, and 12, which encompassed my two trips home. I flew home twice for health-related reasons. The second time, my doctor said that I needed to have surgery. That was 6 weeks before the marathon. (Yes, I’m okay.) I wavered between deciding to skip it and going through with it. In the end, I couldn’t give it up.

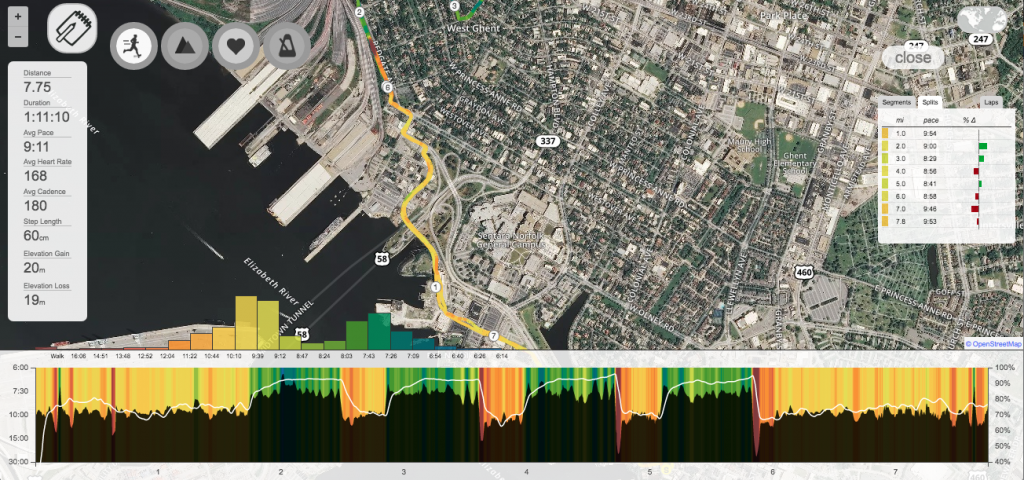

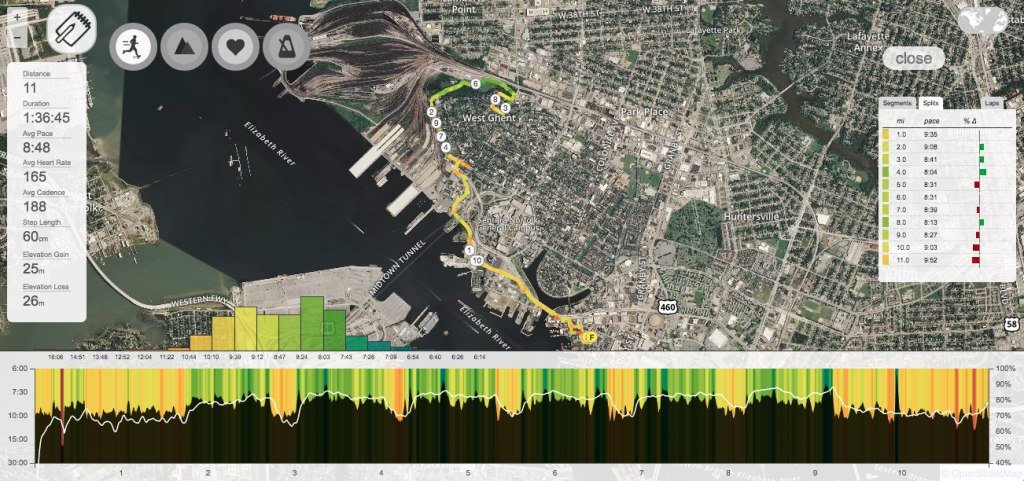

I missed 3 weeks of quality training. Two of those weeks immediately preceded my peak week of marathon training. I missed 3 long runs and 4 SOS runs, which included 2 speed sessions and 2 long tempos. When I resumed training, the season had changed and summer arrived. I struggled to hit my target pace of 8:00min/mi and anchored my remaining tempos to my HR.

The other problem I had is that I trained almost exclusively on flat ground. Zero hills. In my mind, I figured all of my speed training will translate to a successful marathon. I was prepping for a 3:30:00 on flat, but realistically expected to run something between 3:45:00 and 3:51:00 with hills. It seemed reasonable enough. What I obviously didn’t realize then is that there’s no amount of speedwork I can do to replace hill training.

You have to train for the course you choose, and I didn’t do that.

Goals: When I started training for Burlington, my initial goal was a 3:30:00. That’s almost a 10% improvement over Berlin. Calling it a stretch is an understatement. So I revised my expectations halfway into my training and decided that aiming for: (i) anything < 3:51:54, (ii) < 3:47:00 (a 2% improvement), or (iii) < 3:42:00 (a 4% improvement) was more realistic.

Pre-race: Marathoners were scheduled to go at 7:03am. The expected high for the day was 75°F. At 7am, it was about 61°F with 85% relative humidity. You were basically sweating while standing still. I woke up at 5:30am, had a bagel, walked towards the starting line with a double espresso on hand, and jogged the rest of the way.

About 5min before the schedule start time, the race director announced that we needed to evacuate Battery Park. There was a storm front coming in fast and the chief meteorologist of the local news station, who was on site, was able to confirm that there was heavy rain and lightning headed in our direction. Runners were instructed to head down to the Cherry Street parking garage to take shelter and they rescheduled the start time to 7:45am.

The rain that followed made a big difference to the ambient temperature and relative humidity at the start of the race. It was a lot muggier. Starting later also meant a warmer finish for everyone.

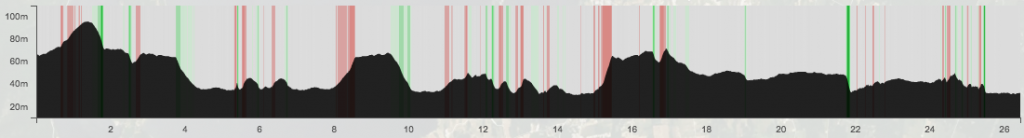

Course: Burlington is a relatively hilly city, and much of the course runs through downtown and along Lake Champlain. Most of the course, probably about 85% of it, is not shaded. You’ll go down a couple of tree-lined streets and cut through parks, but if it’s a clear day – it is virtually impossible to avoid the sun. The course has several moderate rolling hills with one 6-block climb at 6-7.5% grade at Mile 15, finishing with a slight downhill incline to flat. It’s also a clover leaf course, which means a lot of out-and-back.

The opening miles run through downtown and up along the Northern Connector. Once you exit the city, you’re basically out on a closed scenic highway that has a long descent, before climbing up again at the 10k turnaround and then another climb up to reenter the city.

Then it’s a long downhill stretch to South Burlington with several rolling hills around Oakledge Park. The course significantly narrows for the next mile so that only three runners, at most, can run next to each other. Then it opens up and takes you past the rail yard to Battery Street where you can almost sense everyone’s anticipation of the climb back up to Battery Park.

The crowd support at “Assault on Battery” trumps even the best of NYC’s marathon crowds. It’s complete insanity of nonstop cheering and spectators screaming out names and bib numbers. It is overwhelming and exhilarating. You won’t be able to stop yourself from smiling even if you struggle during your ascent. Once you crest the hill, the crowds thin, and you will enter the long lonely stretch of North Avenue.

This is the worst part of the course. You’re basically running abreast one or two other runners, on the side of a busy road where vehicles are allowed one-way, at a slight uphill gradient, for almost 2 miles before turning into a neighborhood. The only thing that redeemed this section of the course is that this mini neighborhood loop had some of the best local support of the entire race. Families handing out water bottles, ice pops, maple syrup shots, gummy bears, pretzels, so many fruits! And then you come back out to North Avenue and turn into Leddy Park.

Ankle deep mud waited for us at Leddy and claimed a few brave runners who decided to run through it. One guy stopped to remove his shoes so he could dump the mud that pooled at his feet. I guess under different circumstances, if Burlington hadn’t had so much rain in the last several weeks, it might have been really nice to cut through this park.

Once you’re through, you make your way back out to North Avenue for another disheartening 1.5 miles before turning in to Burlington’s bike path. From here, the rest of the way is along Lake Champlain, which is slightly uphill for a bit before flattening to the finish.

The Vermont City Marathon finish is just as insane as the climb up Battery Park. For the last mile, it turns into a sidewalk with both sides lined by cheering crowds. I remember feeling pretty good when I finished inside Amsterdam’s olympic stadium, but there is something more exceptional about finishing at Burlington. People seemed genuinely excited to see you, as if they’re your friends and family; completely oblivious to anyone’s misery and only determined to make you feel like you already succeeded.

Splits

| Distance | Pace |

| 5km | 8:15 min/mi |

| 10km | 8:10 min/mi |

| 15km | 8:23 min/mi |

| 20km | 8:35 min/mi |

| 25km | 8:50 min/mi |

| 30km | 9:07 min/mi |

| 35km | 9:39 min/mi |

| 40km | 10:07 min/mi |

| 42km | 9:20 min/mi |

Pacing is critical with a course like Burlington, perhaps more so than flat courses. I spent the day before scoping out parts of the course downtown and knew that the rolling hills were frequent enough that I needed to pace by effort on the uphills and take back what I could on the downhills. The problem with this strategy is that I didn’t really have a good benchmark for what I considered good effort on the uphills.

I kept running within 80-85% of my HRR like I did during training, while trying to take back and bank as much as I could on the downhills. This was a flawed approach from the beginning, because I could never run the downhills fast enough to compensate for what I lost on the uphills. What’s worse is that running every downhill as fast as I could meant that my legs were completely beat up after cresting Battery Park. I pretty much just coasted on whatever I had left until about mile 20 when I picked up a side stitch that I couldn’t shake.

I took 3 gels during the course of the race: one at 15k, 25k, and 35k. This has always worked for me in the past, so I didn’t deviate from it. In addition, I took salt tabs at 10k, 20k, and 30k. I hydrated early and often, drinking only to thirst. (I even learned to run with a paper cup and drink from it!) I also took gatorade at every other aid station from the halfway point to the finish. Even without practice, I feel pretty confident that the problem wasn’t with fueling on the course.

My legs were dead after mile 16 and it was an all-too-familiar feeling. I hit a wall. It took me a while to conclude this because it was the least likely thing I could have messed up, but marathoners know that you usually don’t hit the wall unless you’re glycogen depleted.

It didn’t make sense. Granted, my nutrition has been hit or miss throughout most of the my training, but I ate sensibly the day before race day. And, in the last 3 days leading up to the race, I was having breakfast sandwiches, poke bowls for lunch, and dinner was either lasagna or something with rice.

Another likely culprit is that I didn’t do enough long runs to push through the fatigue. 16 miles is the longest distance I ran on Hansons. It’s possible that without my usual 18 and 20 mile runs, that I inadvertently overreached. I did, after all, miss 3 long runs. Two of those were 16 mile runs. That was definitely an oversight. In retrospect, I probably really needed those runs.

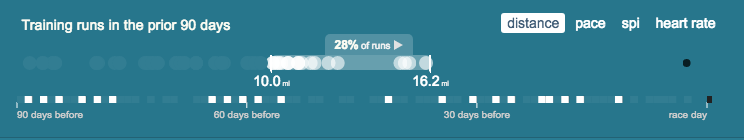

Looking back, I only ran three 15mi runs and one 16mi run, but I had a total of 21 runs over 10mi in the 3 months leading up to Burlington. I only had 15 runs more than 10mi leading up to Berlin. This was a lot more.

Here are the stats compared to my preparation for Berlin.

Race weight: 48kg (same)

10km time pre-marathon: 50:31 (2min 23s slower)

Best Half pre-marathon: 1:46:04 (same)

Best Marathon time pre-Burlington: 3:51:54

In the 3 months leading up to Burlington

Avg Weekly Distance: 44mi (2mi more)

Number of runs per week: 6 (2 more days)

Long runs > 10mi: 21 (6 more runs longer than 10mi)

Long run pace: 9:30min/mi (same)

Longest run distance pre-marathon: 16mi (4 mi less)

Longest run duration pre-marathon: 2:35:34 (38 min 12s less)

I didn’t do a half leading up to Burlington, but I did run my fastest 5mi during a race in March. I also ran my fastest 9mi during a training run in April.

All else considered, the two training cycles were very similar. The only exceptions that I can think of is that I only had one 16mi run, and I expended a lot more effort than I anticipated in the first half of the marathon because of rolling hills. I’m sure the latter meant that I tapped into my glycogen stores way too soon and didn’t have enough to power through the second half of the race.

It’s the worst kind of mistake. The single most important thing I’ve been working since the beginning of this year is pacing and it’s as if I forgot about it on race day. Never again.

I’ll come back for this course.

And I’m gonna crush it.

Yeah. I feel what you say. Hills. I learnt the hard way too that for a marathon with hills, you need a lot (massive) amount of hill work. I’m just impressed how you kept on going despite it all.

I’ve always wondered about Hasons and the lack of really long “long runs”. I suspect for some folk it would work well, but I can’t see it working for me, and in combination with the hills it doesn’t seemed to have worked for you.

But clearly you are a stronger better runner after all of that training you did.

My hat’s off to you.

I’m sure you’ll get it! Mistakes makes us improve in running, in life!

A trick that worked for me to get my marathon PR (without wall) is to know in past editions the runners race pace results (ie barcelona marathon time results splits every 5km) to make the time that I want to achieve.

I try to choose the ones that similar to my running style because I prefer a negative split running. The goal is research a consistent pace throughout the race.

It’s a kind of reverse engineering applied to the marathon circuit to focus the race pace before to the training sessions and automate the effort for race day in the same splits in every tempo/long run.

Of course you need to know the profile of the race and train as closely as possible so that the trick works.

Hope it helps!

My best wishes to your next Marathon PR Jacklyn! Keep on running!